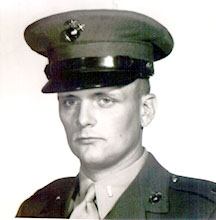

Colonel

Donald G. Cook, USMC

Bath Iron Works' fifteenth ARLEIGH BURKE Class

Destroyer is named in honor of Marine Corps Vietnam War hero, Colonel Donald G.

Cook.† Col. Cook was awarded the Medal of

Honor (posthumously) for his extraordinary courage while a prisoner of war.

Col. (then Captain) Cook volunteered for a temporary 30 day tour in Vietnam as

an observer from Communications Company, Headquarters Battalion, 3rd Marine

Division. Accompanying elements of the 4th Vietnamese Marines, Col. Cook was

wounded and captured by a vastly superior Viet Cong force on New Year's Eve

1964 near Binh Gia, Phouc Tuy Province, South Vietnam, while on a search and

recovery mission for a downed American helicopter crew.† The 33 year old Brooklyn, New York, native and

father of four set an example and standard for his fellow Americans contrary to

the Viet Cong's goal of breaking down the prisoners.† Col. Cook's rigid adherence to the Code of

Conduct won him the respect of his fellow prisoners and his Communist captors.

Donald Cook was the son of Walter and Helen Cook and the brother of

Walter and Irene (Walter passed away in 1960 and Irene Coleman still lives in

N.Y.). They grew up in a strong Catholic family in Brooklyn attending Jesuit

primary and secondary schools.† He

excelled at sports and his exploits on the gridiron earned him the nickname,

"Bayridge Bomber."† Upon

graduation from Xavier High School, Col. Cook enrolled at St. Michael's College

in Winooski, Vermont, where his academic standing was well above average.

Donald Cook was the son of Walter and Helen Cook and the brother of

Walter and Irene (Walter passed away in 1960 and Irene Coleman still lives in

N.Y.). They grew up in a strong Catholic family in Brooklyn attending Jesuit

primary and secondary schools.† He

excelled at sports and his exploits on the gridiron earned him the nickname,

"Bayridge Bomber."† Upon

graduation from Xavier High School, Col. Cook enrolled at St. Michael's College

in Winooski, Vermont, where his academic standing was well above average.

Col. Cook enrolled in the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps but was

subsequently discharged for non-attendance because he had met a beautiful young

woman destined to become his wife, Laurette Giroux of Burlington, Vermont.† Upon graduation in 1956, Col. Cook joined the

Marine Corps Reserve as a private after receiving a special waiver for his lack

of attendance at ROTC and completed Marine Corps Officer's Candidate School at

Quantico, Virginia in 1957. He then attended Communications Officer School and

subsequently served in various communications roles at Camp Pendleton with the

1st Marine Division earning the respect of his superior officers and a regular

commission in the Marine Corps.† Col.

Cook then attended the Chinese Mandarin Language Course at Monterey, California

and the Army Intelligence School at Fort Holabird, Maryland graduating first in

a class of 25.† The next three years

found him serving as the Officer-in-Charge of the 1st Interrogator-Translator

Team with the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing in Hawaii.† It was during this time that Col. Cook

displayed a remarkable fascination with prisoners of war.† He wrote a pamphlet based on the experiences

of American POWs in Korea detailing the Communist interrogation techniques and

he applied those techniques in realistic training scenarios for Marines.† Col. Cook would dress in a Communist uniform

made by his wife and Laurette would use her eyeliner to make Don appear

oriental.† He was an imposing spectacle

to the "captured" Marines.

On 11 December 1964, Col. Cook was reassigned to the Communications

Company, Headquarters Battalion, 3rd Marine Division. That same day, he and

eight other Marines were issued orders to proceed to Saigon, Republic of

Vietnam, and report to the Senior Marine Advisor.† On December 31st, Col. Cook volunteered to

conduct a search and recovery mission for a downed American helicopter and set

off with the 4th Vietnamese Marines.†

Ambushed on their arrival at the crash site, Col. Cook rallied the

Vietnamese Marines who accompanied him, tended to the wounded and was

attempting to drag others to safety when he was wounded in the leg and

captured.† Col. Cook was taken to a Viet

Cong POW camp in the jungles of South Vietnam near the Cambodian border where

he quickly established himself as the senior American (even though he was not)

and provided guidance and strength to his fellow prisoners.† Col. Cook's actions were in direct defiance

of his captors who attempted to remove all semblance of military rank and

structure among the POWs.† He impressed

upon the Viet Cong that he was senior among the POWs and therefore spokesman

for the group, fully aware that his actions would lead to harsh treatment for

himself.† Col. Cook was subjected to

physical abuse and isolation but he resisted his captor's efforts to break his

will and was used as a "bad" example by his Communist guards.† Surviving on limited rations, Col. Cook tried

to maintain his health in his ten foot square cage.† He could be seen by other prisoners

exercising and running for hours.† Once,

while assigned to a work detail with a VC guard, Col. Cook stepped up the pace

to embarrass his captors. Still, the jungle prison took its toll on Col. Cook's

health and he and the other prisoners found themselves in a weakened

state.† Perhaps due to this weakened

condition, Col. Cook contracted malaria shortly before moving to a new

camp.† He was so weak that he staggered

when he walked, could not traverse log bridges, and lost his night vision due to

vitamin deficiency.† Still, he persevered,

refusing to allow anyone to carry his pack or otherwise put a strain on

themselves to help him.† By the time the

new camp was reached, even the camp commander complimented Col. Cook on his

courage.† Although he regained some of

his strength at the new camp, Col. Cook still suffered from the effects of

malaria.† As illness struck the other

prisoners, Col. Cook unhesitatingly took on the bulk of their workloads in

order that they might have time to recover.†

His knowledge of first aid prompted him to nurse the severely sick by

administering heart massage, moving limbs, and keeping men's tongues from

blocking their air passages.† He was

instrumental in saving the lives of several POWs who were convulsing with

severe malaria attacks.

On 11 December 1964, Col. Cook was reassigned to the Communications

Company, Headquarters Battalion, 3rd Marine Division. That same day, he and

eight other Marines were issued orders to proceed to Saigon, Republic of

Vietnam, and report to the Senior Marine Advisor.† On December 31st, Col. Cook volunteered to

conduct a search and recovery mission for a downed American helicopter and set

off with the 4th Vietnamese Marines.†

Ambushed on their arrival at the crash site, Col. Cook rallied the

Vietnamese Marines who accompanied him, tended to the wounded and was

attempting to drag others to safety when he was wounded in the leg and

captured.† Col. Cook was taken to a Viet

Cong POW camp in the jungles of South Vietnam near the Cambodian border where

he quickly established himself as the senior American (even though he was not)

and provided guidance and strength to his fellow prisoners.† Col. Cook's actions were in direct defiance

of his captors who attempted to remove all semblance of military rank and

structure among the POWs.† He impressed

upon the Viet Cong that he was senior among the POWs and therefore spokesman

for the group, fully aware that his actions would lead to harsh treatment for

himself.† Col. Cook was subjected to

physical abuse and isolation but he resisted his captor's efforts to break his

will and was used as a "bad" example by his Communist guards.† Surviving on limited rations, Col. Cook tried

to maintain his health in his ten foot square cage.† He could be seen by other prisoners

exercising and running for hours.† Once,

while assigned to a work detail with a VC guard, Col. Cook stepped up the pace

to embarrass his captors. Still, the jungle prison took its toll on Col. Cook's

health and he and the other prisoners found themselves in a weakened

state.† Perhaps due to this weakened

condition, Col. Cook contracted malaria shortly before moving to a new

camp.† He was so weak that he staggered

when he walked, could not traverse log bridges, and lost his night vision due to

vitamin deficiency.† Still, he persevered,

refusing to allow anyone to carry his pack or otherwise put a strain on

themselves to help him.† By the time the

new camp was reached, even the camp commander complimented Col. Cook on his

courage.† Although he regained some of

his strength at the new camp, Col. Cook still suffered from the effects of

malaria.† As illness struck the other

prisoners, Col. Cook unhesitatingly took on the bulk of their workloads in

order that they might have time to recover.†

His knowledge of first aid prompted him to nurse the severely sick by

administering heart massage, moving limbs, and keeping men's tongues from

blocking their air passages.† He was

instrumental in saving the lives of several POWs who were convulsing with

severe malaria attacks.

Even though he was on half-rations, Col. Cook

shared his food with the weaker POWs, even giving up his allowance of

penicillin.† Because he was isolated,

Col. Cook devised a drop-off point for communications, instructing his fellow

POWs to continue resistance and offering the means to do so. Time and again he refused to negotiate for his own release knowing full

well it would mean his imprisonment for the entire war.† After a failed escape attempt, a gun was held

to his head and Col. Cook calmly recited the pistol's nomenclature showing no

fear whatsoever.† Surely he knew that in

his deteriorated condition that he would not survive a long imprisonment yet he

continued to offer food and badly needed medicine to other POWs.† In this respect, he went far above and beyond

the call of duty by risking his life to inspire other POWs to survive.† Col. Donald G. Cook was last seen on a jungle

trail by a fellow American prisoner, Douglas Ramsey, in November 1967.† When Mr. Ramsey was released in 1973, he was

told that Col. Cook had died from malaria on 8 December 1967 while still in

captivity.† No remains were ever returned

by the Vietnamese government.† On 26

February 1980, Col. Cook was declared dead under the Missing Service Persons

Act of 1942.† On 15 May 1980, a memorial

stone was placed in Arlington National Cemetery and the flag from the empty

grave presented to his wife, Laurette.†

The following day Colonel Donald G. Cook was posthumously awarded the

Medal of Honor. The ship's motto, "Faith Without Fear" epitomizes his

courage and faith in God and country.

Colonel Donald Gilbert Cook

On 30

September 2007 St. Michaelís College unveiled and dedicated a life-sized

granite statue of Col. Cook that stands in a commanding location at the

entrance of the Military Heritage Memorial, near the main entrance to the

college.† The Military Heritage Memorial

remembers all of the Collegeís alumni veterans.†

On the reverse of the base is the inscription

IN HONOR OF

THE MILITARY SERVICE

OF MEMBERS OF THE

SAINT MICHAELíS COLLEGE COMMUNITY

Medal of Honor citation

For conspicuous gallantry

and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while

interned as a Prisoner of War by the Viet Cong in the

Republic of Vietnam during the period 31 December 1964 to 8 December 1967.

Despite the fact that by so doing he would bring about harsher treatment for

himself, Colonel (then Captain) Cook established himself as the senior

prisoner, even though in actuality he was not. Repeatedly assuming more than

his share of responsibility for their health, Colonel Cook willingly and

unselfishly put the interests of his comrades before that of his own well-being

and, eventually, his life. Giving more needy men his medicine and drug

allowance while constantly nursing them, he risked infection from contagious

diseases while in a rapidly deteriorating state of health. This unselfish and

exemplary conduct, coupled with his refusal to stray even the slightest from the

Code of Conduct, earned him the deepest

respect from not only his fellow prisoners, but his captors as well. Rather

than negotiate for his own release or better treatment, he steadfastly

frustrated attempts by the Viet Cong to break his indomitable spirit and passed

this same resolve on to the men whose well-being he so closely associated

himself. Knowing his refusals would prevent his release prior to the end of the

war, and also knowing his chances for prolonged survival would be small in the

event of continued refusal, he chose nevertheless to adhere to a Code of

Conduct far above that which could be expected. His personal valor and

exceptional spirit of loyalty in the face of almost certain death reflected the

highest credit upon Colonel Cook, the Marine Corps, and the United States Naval

Service.

††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††

The USS

Donald Cook DDG75 is the first naval war vessel named for an unreturned

Prisoner of War.† On 20 March 2003 the

first Tomahawk missiles launched at the beginning of the Second Gulf War were

fired from the USS Donald Cook.† More

information about the ship is available at††

USS Donald Cook.

More

pictures† here.